In the past, celebrity deaths haven’t affected me much. Typically, I might pause a moment, revisit an artist’s work, or take in others’ stories of the connections they had felt, aware that even with many of my favorite artists, I’d never felt connected in quite the same way. I suppose in many cases I don’t have a sense that I really share the same world or exist in the same reality as the artists I admire. They reach me through their art, a vehicle that mediates what I consider an otherwise healthy distance.

That distance shattered in the hours after I heard about SOPHIE’s death. I spent some time revisiting the artist’s work and texting friends—most of them other trans girls who I knew would feel affected and had an even closer connection to SOPHIE’s work and being than myself.

I reminisced upon hearing “HARD” for the first time in 2014. I remembered how I clinged to the song for years before my own transition, realizing it had opened an aesthetic world up for me when I still had much to realize about myself. Rebecca and I marveled at the playfully sexy choreography in the video for “PONYBOY,” the adorable moment when SOPHIE wields a tube of cherry red lipstick and pulls it away without applying, exhaling vapor. Then, we braved the video for “It’s Okay To Cry,” staring into SOPHIE’s glimmering eyes, half naked and baring an unprocessed, full, and elegant voice. We marveled as we reminisced how the video served as a public coming out.

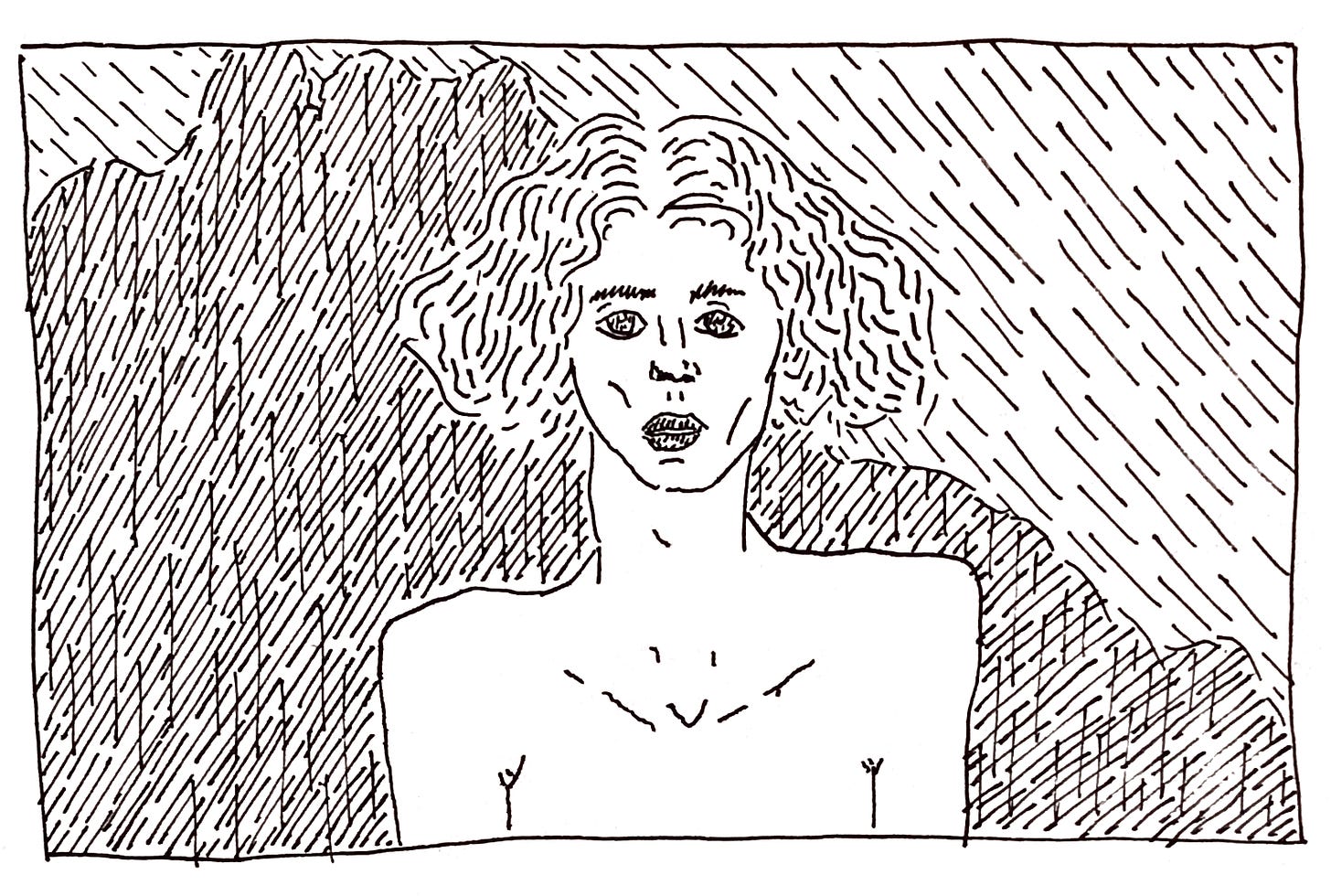

After the dazzling display of SOPHIE’s outpouring, bare shoulders and chest floating against a backdrop of galaxies and rain, I clicked over to a Grammy red carpet interview, eager to witness the statuesque figure and voice in a public setting, a figure and voice both feminine in the ways I wish to be feminine—that is, transfeminine, wholly and unapologetically.

I watched, smiling, as SOPHIE gracefully responded to the interviewer’s questions about the nomination—sharing expectations, playfully teasing info of future collaborations, joyfully relaying the response of a grandmother—when an unfortunate but rather quotidian infraction occurred.

The interviewer barrelled through a sentence and clearly (if subtly) misgendered SOPHIE before quickly rephrasing the sentence foregoing pronouns altogether. I watched SOPHIE remain poised, seemingly unfettered, but suddenly quiet, taking pause before speaking. Then, too deep with sympathy for the artist at this moment, I closed the window without watching the rest, silently breaking into tears for the first time since finding out about the artist’s untimely death.

Like most instances of misgendering, the moment was quick and accidental. The words around it had nothing but the best intentions. But one word can carry with it a million internal voices. It can be a denial, a reminder, an albatross around one’s neck; it can force one to question what they were sure of or had not even thought to consider just a moment before; a completely ordinary act of erasure committed before one’s eyes.

SOPHIE’s management, it should be said, has asked the press to refrain from the use of pronouns whatsoever, a request that only emphasizes the weight that pronouns hold and highlights the vastness of the artist’s experience of gender.

As singer, composer, and visual artist Anohni once wrote, “I think words are important. To call a person by their chosen gender is to honor their spirit, their life and contribution. ‘He’ is an invisible pronoun for me, it negates me.”

Watching SOPHIE become the collateral of a careless slip of the tongue while in a moment of fond remembrance was devastating. But in that moment, I found SOPHIE to be more real to me than any celebrity had ever been.

If there was any hope for trans girls to escape the travails of daily trans life, SOPHIE represented it. If there was ever a sense that SOPHIE wasn’t trans, but SOPHIE (to borrow a line commonly attributed to O.J. Simpson), this small moment, this microaggression, was there to remind the innovator that wasn’t the case.

I spent the remainder of that night with a pit in my gut. Here was a person presenting in a way I wished to embody some part of, and suddenly, I realized how much more of a common experience that means we shared in this world.

It is no coincidence that several of the handful of highly influential transfeminine people in music have, like SOPHIE, had a habit of staying out of the limelight. Little barbs like these can be even more painful, especially when they play out in the public eye.

Unfortunately, this misgendering wasn’t the only familiar information I had to process yesterday. Trans death is terribly visible. The oft-cited statistic that “the average life expectancy of trans women of color in the U.S. is only 35” isn’t quite correct, but its wide circulation tells its own sort of truth: that we are too used to seeing trans women die young in our media and, as such, are conditioned to believe such a horrifying number.

SOPHIE’s death, as it has been reported, seems cruelly senseless, banal, and completely beside the fact of the artist’s transness. What it means for those of us watching, however, is that we’ll never have a chance to see one of our few modern idols and creative geniuses come into old age and develop over a lifetime. We are deprived of one more face to look up to and one more voice to help us find new ways to speak.

Now, each time one of SOPHIE’s sugary hooks forces its way back into my mind, it carries with it more than an ounce of pain. An untimely death has taken away an icon and a bright and hopeful musical future, but, most affectingly for me, it has taken away a rare living figure in whom I could see myself.

Postscript:

While researching this piece I came across composer, arranger, and orchestrator Angela Morley. Born in 1924, Morley was the first openly transgender person to be nominated for an academy award following her transition in 1970. Also of interest is her work as an arranger on the albums Scott, Scott 2, and Scott 3. Notably, she has also worked with top-bill names John Williams, Yo-Yo Ma, and Itzhak Perlman.

Baffled that I hadn’t heard of her before, I immediately texted my friend Cassie. We took in her astoundingly gorgeous and thorough website, sharing tidbits and favorite images. We learned that at the end of her life she moved to Scottsdale, AZ, where she lived with her wife, singer Christine Parker, who had helped her through her transition decades before. As Morley once stated, “It was only because of her love and support that I was able to deal with the trauma and begin to think about crossing over that terrifying gender border.”

As we did this, Cassie remarked how healing it felt. Representation and history are fraught areas for trans people, often full of landmines, gaps in knowledge, and terrible tragedy. Here was a woman who had made it and had lived an almost startlingly average life. I share her story here to remind myself of those who have made it, who outlasted the daily tragedies.

~ thank you for reading, and thanks, as always, to Rebecca Jones for their editorial assistance. the Winter edition of Happiness Journal will arrive in your inbox in the coming weeks ~